Related Work¶

At first sight, Triton may seem like just yet another DSL for DNNs. The purpose of this section is to contextualize Triton and highlight its differences with the two leading approaches in this domain: polyhedral compilation and scheduling languages.

Polyhedral Compilation¶

Traditional compilers typically rely on intermediate representations, such as LLVM-IR [LATTNER2004], that encode control flow information using (un)conditional branches. This relatively low-level format makes it difficult to statically analyze the runtime behavior (e.g., cache misses) of input programs, and to automatically optimize loops accordingly through the use of tiling [WOLFE1989], fusion [DARTE1999] and interchange [ALLEN1984]. To solve this issue, polyhedral compilers [ANCOURT1991] rely on program representations that have statically predictable control flow, thereby enabling aggressive compile-time program transformations for data locality and parallelism. Though this strategy has been adopted by many languages and compilers for DNNs such as Tiramisu [BAGHDADI2021], Tensor Comprehensions [VASILACHE2018], Diesel [ELANGO2018] and the Affine dialect in MLIR [LATTNER2019], it also comes with a number of limitations that will be described later in this section.

Program Representation¶

Polyhedral compilation is a vast area of research. In this section we only outline the most basic aspects of this topic, but readers interested in the solid mathematical foundations underneath may refer to the ample literature on linear and integer programming.

for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

for(int j = i; j < 5; j++)

A[i][j] = 0;

|

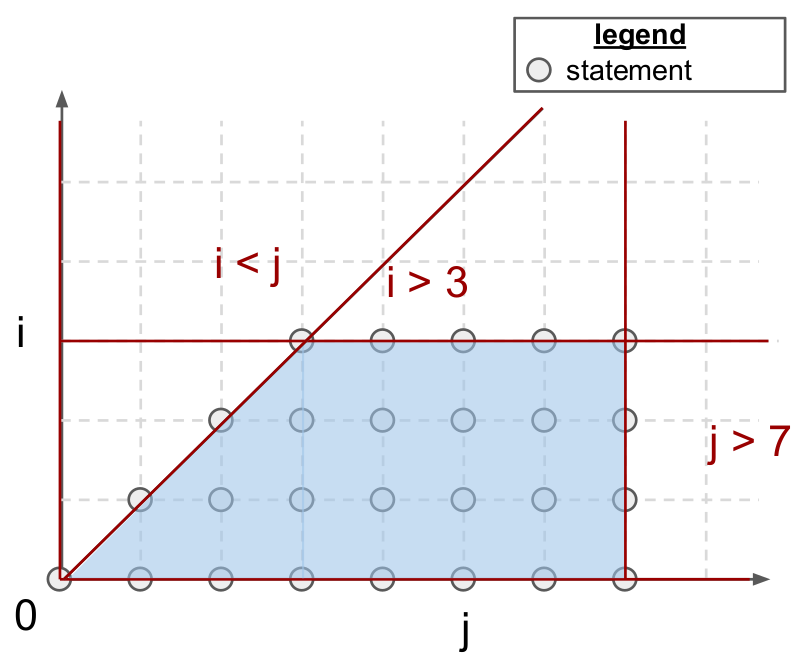

Polyhedral compilers focus on a class of programs commonly known as Static Control Parts (SCoP), i.e., maximal sets of consecutive statements in which conditionals and loop bounds are affine functions of surrounding loop indices and global invariant parameters. As shown above, programs in this format always lead to iteration domains that are bounded by affine inequalities, i.e., polyhedral. These polyhedra can also be defined algebraically; for the above example:

Each point \((i, j)\) in \(\mathcal{P}\) represents a polyhedral statement, that is a program statement which (1) does not induce control-flow side effects (e.g., for, if, break) and (2) contains only affine functions of loop indices and global parameters in array accesses. To facilitate alias analysis, array accesses are also mathematically abstracted, using so-called access function. In other words, A[i][j] is simply A[f(i,j)] where the access function \(f\) is defined by:

Note that the iteration domains of an SCoP does not specify the order in which its statements shall execute. In fact, this iteration domain may be traversed in many different possible legal orders, i.e. schedules. Formally, a schedule is defined as a p-dimensional affine transformation \(\Theta\) of loop indices \(\mathbf{x}\) and global invariant parameters \(\mathbf{g}\):

Where \(\Theta_S(\mathbf{x})\) is a p-dimensional vector representing the slowest to fastest growing indices (from left to right) when traversing the loop nest surrounding \(S\). For the code shown above, the original schedule defined by the loop nest in C can be retrieved by using:

where \(i\) and \(j\) are respectively the slowest and fastest growing loop indices in the nest. If \(T_S\) is a vector (resp. tensor), then \(\Theta_S\) is a said to be one-dimensional (resp. multi-dimensional).

Advantages¶

Programs amenable to polyhedral compilation can be aggressively transformed and optimized. Most of these transformations actually boil down to the production of schedules and iteration domains that enable loop transformations promoting parallelism and spatial/temporal data locality (e.g., fusion, interchange, tiling, parallelization).

Polyhedral compilers can also automatically go through complex verification processes to ensure that the semantics of their input program is preserved throughout this optimization phase. Note that polyhedral optimizers are not incompatible with more standard optimization techniques. In fact, it is not uncommon for these systems to be implemented as a set of LLVM passes that can be run ahead of more traditional compilation techniques [GROSSER2012].

All in all, polyhedral machinery is extremely powerful, when applicable. It has been shown to support most common loop transformations, and has indeed achieved performance comparable to state-of-the-art GPU libraries for dense matrix multiplication [ELANGO2018]. Additionally, it is also fully automatic and doesn’t require any hint from programmers apart from source-code in a C-like format.

Limitations¶

Unfortunately, polyhedral compilers suffer from two major limitations that have prevented its adoption as a universal method for code generation in neural networks.

First, the set of possible program transformations \(\Omega = \{ \Theta_S ~|~ S \in \text{program} \}\) is large, and grows with the number of statements in the program as well as with the size of their iteration domain. Verifying the legality of each transformation can also require the resolution of complex integer linear programs, making polyhedral compilation very computationally expensive. To make matters worse, hardware properties (e.g., cache size, number of SMs) and contextual characteristics (e.g., input tensor shapes) also have to be taken into account by this framework, leading to expensive auto-tuning procedures [SATO2019].

Second, the polyhedral framework is not very generally applicable; SCoPs are relatively common [GIRBAL2006] but require loop bounds and array subscripts to be affine functions of loop indices, which typically only occurs in regular, dense computations. For this reason, this framework still has to be successfully applied to sparse – or even structured-sparse – neural networks, whose importance has been rapidly rising over the past few years.

On the other hand, blocked program representations advocated by this dissertation are less restricted in scope and can achieve close to peak performance using standard dataflow analysis.

Scheduling Languages¶

Separation of concerns [DIJKSTRA82] is a well-known design principle in computer science: programs should be decomposed into modular layers of abstraction that separate the semantics of their algorithms from the details of their implementation. Systems like Halide and TVM push this philosophy one step further, and enforce this separation at the grammatical level through the use of a scheduling language. The benefits of this methodology are particularly visible in the case of matrix multiplication, where, as one can see below, the definition of the algorithm (Line 1-7) is completely disjoint from its implementation (Line 8-16), meaning that both can be maintained, optimized and distributed independently.

1// algorithm

2Var x("x"), y("y");

3Func matmul("matmul");

4RDom k(0, matrix_size);

5RVar ki;

6matmul(x, y) = 0.0f;

7matmul(x, y) += A(k, y) * B(x, k);

8// schedule

9Var xi("xi"), xo("xo"), yo("yo"), yi("yo"), yii("yii"), xii("xii");

10matmul.vectorize(x, 8);

11matmul.update(0)

12 .split(x, x, xi, block_size).split(xi, xi, xii, 8)

13 .split(y, y, yi, block_size).split(yi, yi, yii, 4)

14 .split(k, k, ki, block_size)

15 .reorder(xii, yii, xi, ki, yi, k, x, y)

16 .parallel(y).vectorize(xii).unroll(xi).unroll(yii);

The resulting code may however not be completely portable, as schedules can sometimes rely on execution models (e.g., SPMD) or hardware intrinsics (e.g., matrix-multiply-accumulate) that are not widely available. This issue can be mitigated by auto-scheduling mechanisms [MULLAPUDI2016].

Advantages¶

The main advantage of this approach is that it allows programmers to write an algorithm only once, and focus on performance optimization separately. It makes it possible to manually specify optimizations that a polyhedral compiler wouldn’t be able to figure out automatically using static data-flow analysis.

Scheduling languages are, without a doubt, one of the most popular approaches for neural network code generation. The most popular system for this purpose is probably TVM, which provides good performance across a wide range of platforms as well as built-in automatic scheduling mechanisms.

Limitations¶

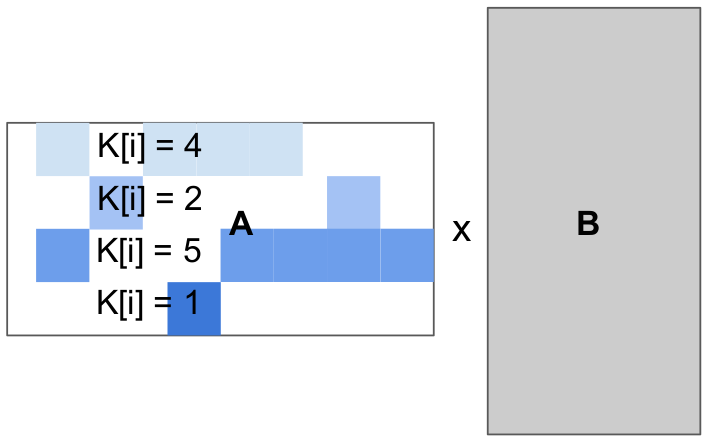

This ease-of-development comes at a cost. First of all, existing systems that follow this paradigm tend to be noticeably slower than Triton on modern hardware when applicable (e.g., V100/A100 tensor cores w/ equal tile sizes). I do believe that this is not a fundamental issue of scheduling languages – in the sense that it could probably be solved with more efforts – but it could mean that these systems are harder to engineer. More importantly, existing scheduling languages generate loops whose bounds and increments cannot depend on surrounding loop indices without at least imposing severe constraints on possible schedules – if not breaking the system entirely. This is problematic for sparse computations, whose iteration spaces may be irregular.

for(int i = 0; i < 4; i++)

for(int j = 0; j < 4; j++)

float acc = 0;

for(int k = 0; k < K[i]; k++)

acc += A[i][col[i, k]] * B[k][j]

C[i][j] = acc;

|

On the other hand, the block-based program representation that we advocate for through this work allows for block-structured iteration spaces and allows programmers to manually handle load-balancing as they wish.

References¶

Lattner et al., “LLVM: a compilation framework for lifelong program analysis transformation”, CGO 2004

Wolfe, “More Iteration Space Tiling”, SC 1989

Darte, “On the Complexity of Loop Fusion”, PACT 1999

Allen et al., “Automatic Loop Interchange”, SIGPLAN Notices 1984

Ancourt et al., “Scanning Polyhedra with DO Loops”, PPoPP 1991

Baghdadi et al., “Tiramisu: A Polyhedral Compiler for Expressing Fast and Portable Code”, CGO 2021

Vasilache et al., “Tensor Comprehensions: Framework-Agnostic High-Performance Machine Learning Abstractions”, ArXiV 2018

Elango et al. “Diesel: DSL for Linear Algebra and Neural Net Computations on GPUs”, MAPL 2018

Lattner et al., “MLIR Primer: A Compiler Infrastructure for the End of Moore’s Law”, Arxiv 2019

Grosser et al., “Polly - Performing Polyhedral Optimizations on a Low-Level Intermediate Representation”, Parallel Processing Letters 2012

Sato et al., “An Autotuning Framework for Scalable Execution of Tiled Code via Iterative Polyhedral Compilation”, TACO 2019

Girbal et al., “Semi-Automatic Composition of Loop Transformations for Deep Parallelism and Memory Hierarchies”, International Journal of Parallel Programming 2006

Dijkstra et al., “On the role of scientific thought”, Selected writings on computing: a personal perspective 1982

Mullapudi et al., “Automatically scheduling halide image processing pipelines”, TOG 2016